How Valuable is the Indian River Lagoon?

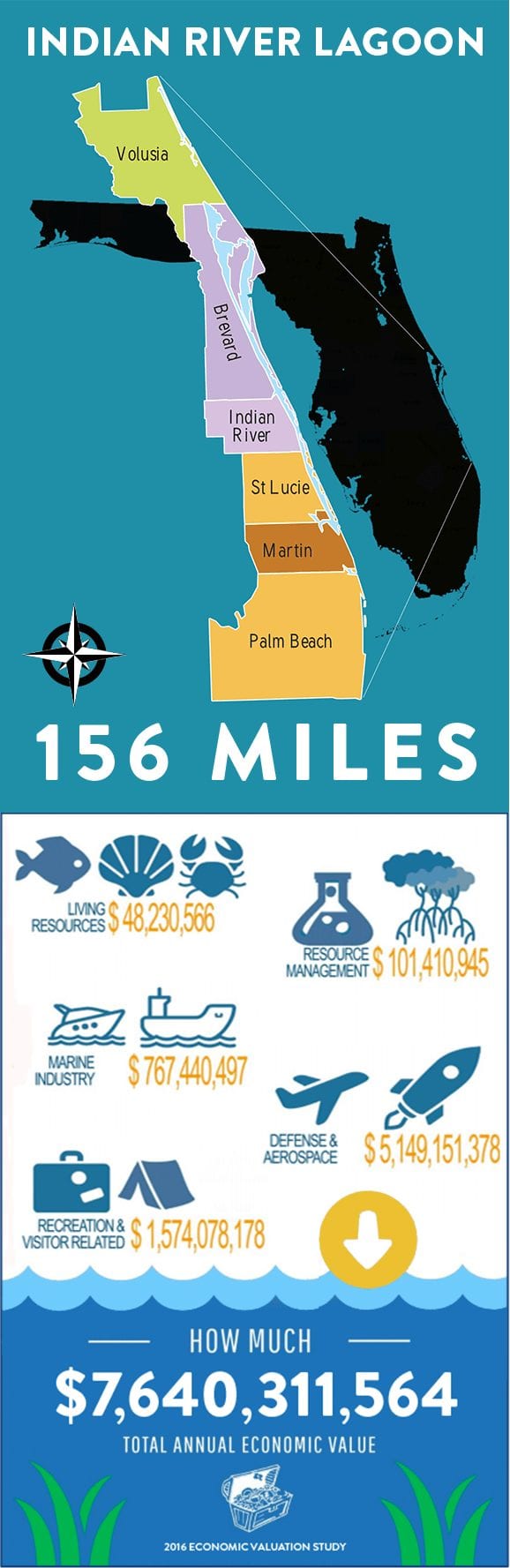

The Indian River Lagoon (IRL) is part of the longest barrier island complex in North America, occupying more than 40% of Florida’s east coast, extending over 156 miles from Ponce de Leon Inlet to Jupiter Inlet in West Palm Beach. The Lagoon is a uniquely diverse water way encompassing three bodies of water, the Mosquito Lagoon, Banana River and the Indian River.

These bodies of water are not actually rivers as they have no headwaters and no mouths and their flow relies on wind and tidal currents. Instead, the Indian River Lagoon is an estuary, where fresh water combines with ocean salt water through inlets creating a complex collage of habitat and biological diversity.

As one of the most biologically diverse estuaries in North America, the IRL is home to more than 4,000 species of plants and animals that depend on the quality of water within the Lagoon for survival.

The IRL is a significant economic driver for five counties—Volusia, Brevard, Indian River, St. Lucie and Martin counties. In a recent 2016 economic valuation study by the East Central Florida and Treasure Coast Regional Planning Councils, the IRL’s total economic output in 2014 was $7.6 billion, not including an estimated $934 million in annualized real estate value for properties located on or near the lagoon.

The Lagoon has experienced countless algal blooms since 2011, which have destroyed more than 60% of its seagrasses and killed off record numbers of manatees, pelicans, dolphins, shorebirds and fish. Today we have lost most more than 50% of our native species who call the Lagoon home.

Why is the Indian River Lagoon Sick?

For decades, the IRL has been severely threatened by rapid development, habitat destruction, overharvesting and pollution. The northern half of the Lagoon has only a few outlets to the sea, so it does not flush very rapidly which means that stormwater runoff, wastewater treatment discharges, septic systems and excess fertilizer applications have flooded the Lagoon with harmful nutrients and sediments. The nutrients feed the massive algal blooms, and together, with the suspended particles, block the sun from reaching the seagrass. As a result, the seagrass dies, oxygen levels fall and fish suffocate. The rotting fish produce more available nutrients which leads to more blooms.

Help Us Restore Our Shores

Sign up for our newsletter, learn lagoon habits, and help us take action to restore living shorelines in Brevard